|

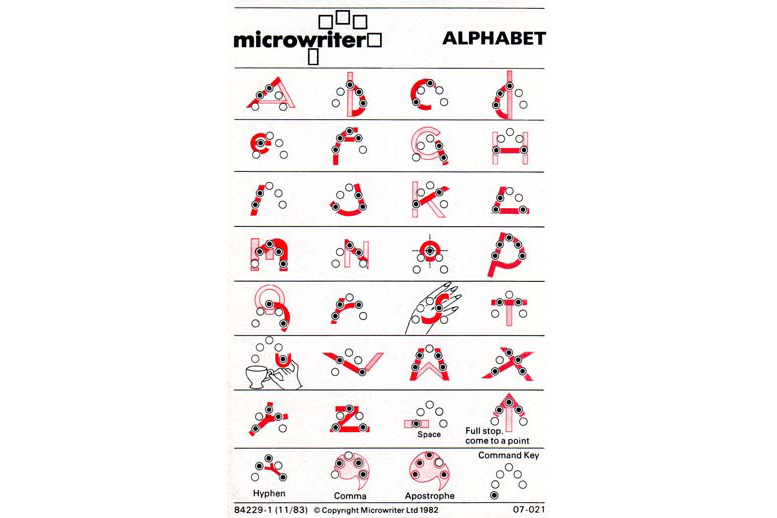

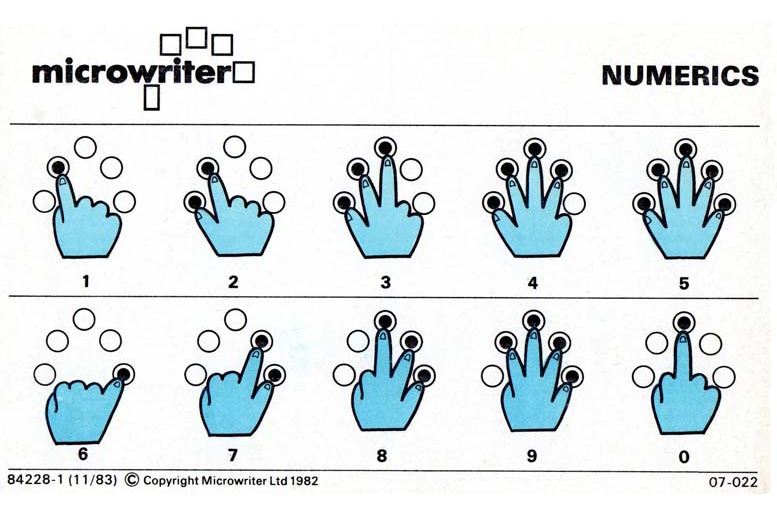

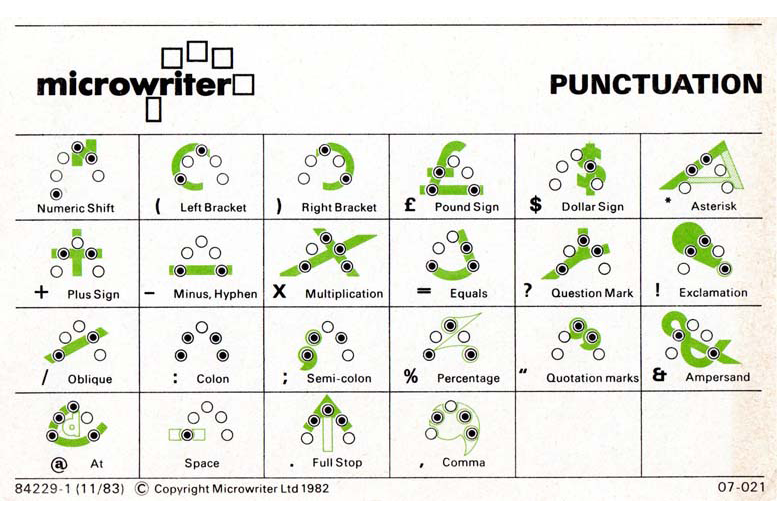

Microwriter      Bill Buxton's NotesMy Microwriter is one of my favourite things in my collection, one that I have had the longest, and one that I used the most. It is also on that taught me the most – both in terms of facts, but also in terms of appreciating the difference between intellectual and experiential learning. That is, I gained insights about the subtleties and nature of human skill from it that I would not have gotten from the literature alone, and through that, a lesson that has stood me in good stead ever since. The Microwriter was, I believe, the world’s first portable digital word processor. It was first shown in 1978. This unit dates from circa 1980. One types with a 6 button one-handed chording keyboard. That is, your fingers are always in “home position” (the thumb being the only digit to alternate between two keys) and you enter text by pushing combinations of buttons, or “chords”. Hence, you could (and I would) stand in the subway, hold on to the car for balance with one hand, and type with the other. I just needed to hold the device against my chest with the palm of the same hand that I typed with. It could also be connected to your PC as a substitute for your QWERTY keyboard. My one complaint is that that I always felt that the right-handed version should be used in the left hand, rather than the right. Why? For the same reason that Engelbart used his chord keyboard in the non-dominant hand: so that the dominant hand could be utilized for pointing and selecting, using a mouse for example, when working at one’s desk. This desire to use it in either hand led to another observation around the mnemonics used in teaching the chording scheme. Yes, my unit still works, and one can learn to touch type in about 60 minutes (a good thing, since one rapidly discovers that with chord keyboards, there is no hunt-and-peck option; you can either touch type or you can’t type at all). But look at the materials that are given to teach you how to type. Here we see something really interesting. Look at the aids used to remember the following letters. In each case, the character (in red) is drawn over a stylized representation, and inverted V shape, of the positions of the five digits of the right hand:

There are three really fascinating things that pop if you consider even these three cases carefully:

I am conflicted in all of this. Why? Because on the one hand, I think that the New User’s Guide is one of the best examples of technical writing that I have ever seen in a user’s manual. I love the parallel use of different representations to get the message across. I really appreciated it when I was learning, and think that the manual is worth studying for its approach (compare it to those produced for the other chord keyboards that I discuss, as a really good exercise!). On the other hand, there is this issue that, in preparing the pedagogical approach, and the associated mental models that would result, they did not anticipate using the device in either or both hands, and thereby inadvertently built in some road-blocks. This is understandable, given that the design was done before the mouse was commercially available, much less the GUI. But that just signals all the more need for caution and looking further forward in our own decisions – which risk falling into the same trap. One that – when you move to looking at the Microwriter’s descendent, the CyKey (which is designed to be used by either hand), the Microwriter decisions ran into at full steam. In the larger scheme of things, not a huge problem. But a problem nevertheless. I still have a soft-spot for this device, and everything that it represents! Bill Buxton Device Details

Company: Microwriter |

Year: 1978 |